Last week, our team -HauDong ft.Art visited the Vietnamese Women’s Museum in Hanoi to explore its Mother Goddess Worship exhibit, part of the museum’s commitment to preserving and presenting Vietnam’s intangible cultural heritage. What I saw there left a deep impression—this was not just a display of artifacts, but a living tradition, blending art, faith, history, and community.

As soon as I entered the exhibit space, I was struck by how atmospheric it had been arranged: soft lighting, quiet voices on audio guides, and subtle incense aroma in some corners. The exhibition is part of a program called “Mother Goddess: Pure Heart – Beauty – Joy”, through which the museum offers visitors a sensorial introduction to Đạo Mẫu and hầu đồng performances.

Encountering Beliefs: The World of Đạo Mẫu

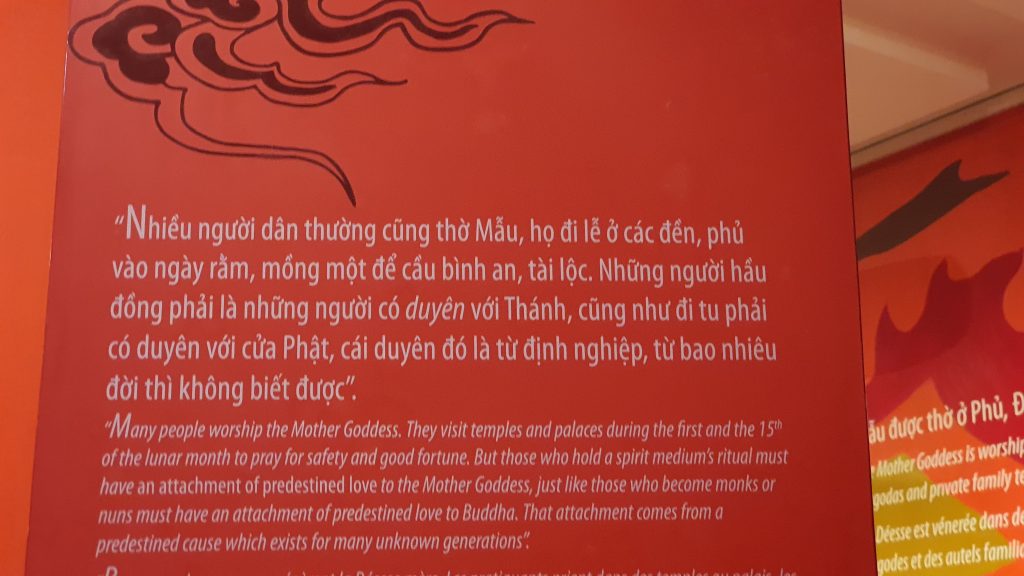

Before seeing the objects, I listened to audio guides and read panels that explained the theological framework. Đạo Mẫu (Mother Goddess Worship) is a Vietnamese folk religious tradition, developed since at least the 16th century, that honors female deities, ancestral spirits, legendary heroines, and nature spirits.

Central to this tradition is the ritual known as hầu đồng (sometimes called lên đồng). In hầu đồng, trained spirit mediums (called thanh đồng) enact and embody various divine figures through costume changes, dance, music, and poetry. While many think of hầu đồng merely as spirit possession, in this practice the medium remains in conscious control; the ritual is more performance than passive channeling.

One striking feature is that the pantheon includes goddesses of multiple domains: Heaven, Water, Forests & Mountains, and Earth. In many temples, the ritual proceeds through a sequence of incarnations—each deity has a costume color, signature gestures, and accompanying songs.

Art, Ritual, and Symbolism

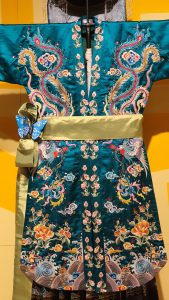

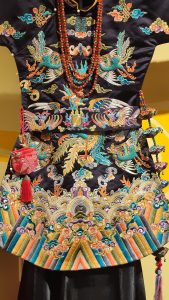

Walking from display to display, I saw the exquisite costumes worn by mediums in actual ceremonies. Each outfit was rich in embroidery—dragons, phoenixes, clouds, waves—and made of colorful silk. The colors had meaning: for example, green might indicate a forest or mountain deity, white for water spirits.

Alongside the robes were delicate jewelry: silver necklaces, hairpins, earrings—each piece not only decorative but symbolic, enhancing the spiritual transformation of the medium. The exhibit also included miniature dolls representing deities, ritual objects, and detailed altar setups.

One of the most compelling displays showed musical instruments: drums, bronze gongs, flutes, stringed instruments (like the đàn nguyệt), and sets of chầu văn hymn music. These instruments and music are essential: they call the deities to descend, accompany each incarnation, and drive the rhythm of the ritual.

Experiencing the Ritual

During our visit, we were fortunate to attend a short demonstration of hầu đồng as part of the museum’s cultural offering. The performance lasted about 90 minutes and took place in a ceremonial space within the exhibit.

The medium entered slowly, dressed in a white costume to represent a neutral stage. With the rising tones of chầu văn music and soft lighting, the first incarnation was called. With each change, assistants helped the medium switch robes, don new headdresses, wield symbolic props (fans, swords, banners). The medium shifted posture and gestures to honor each deity’s character—some movements were martial and strong, others graceful and serene.

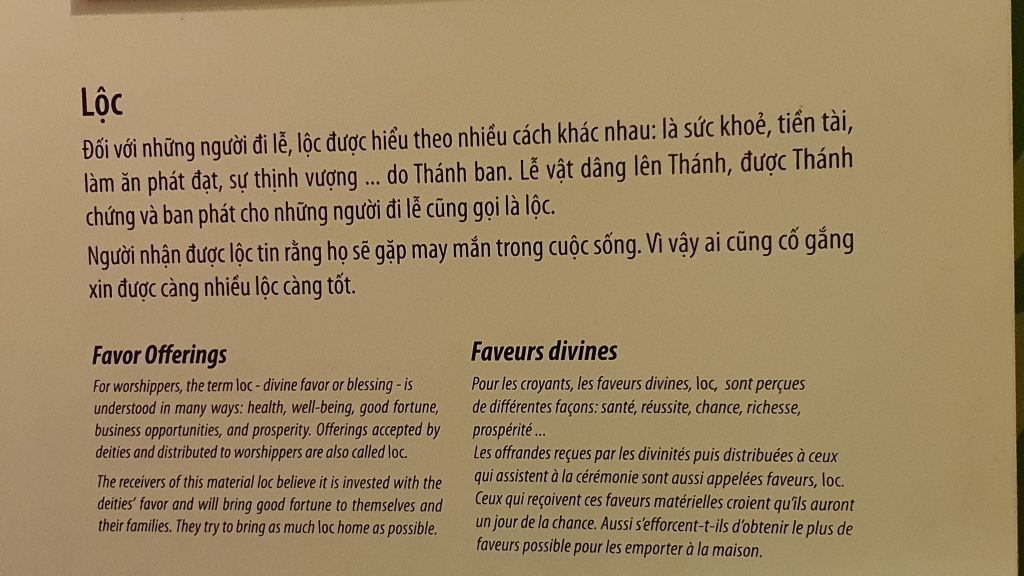

I sensed the audience leaning forward, entranced. At moments, coins or votive money were offered by the medium to participants—called lộc, sacred gifts believed to carry divine blessings.

Watching that, I realized hầu đồng is more than spectacle: it becomes a bridge linking worshipper and divine, myth and everyday life. The performance made stories, faith, and identity tangible.

Reflections and Cultural Significance

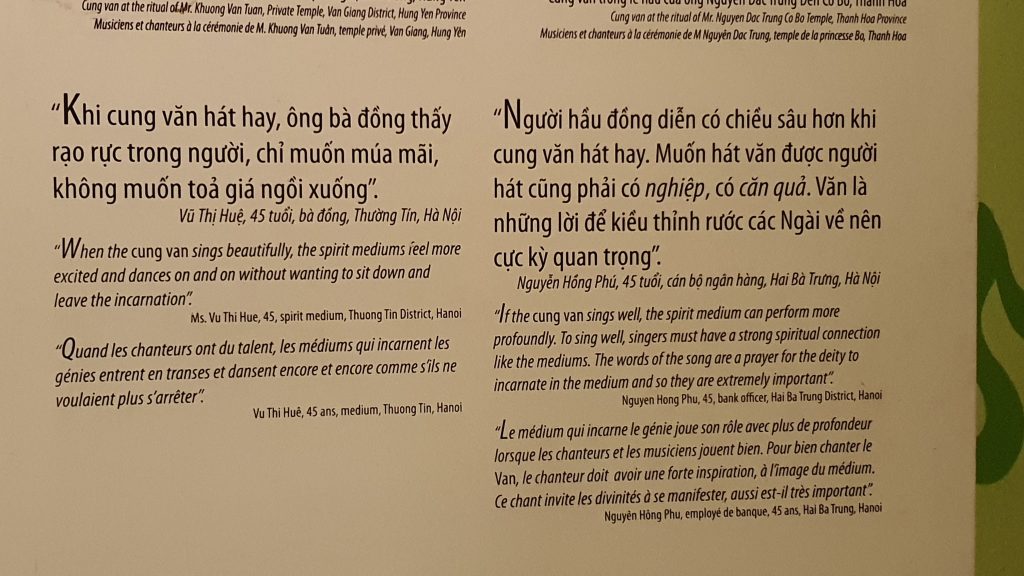

Afterward, I spent time reading personal testimonies displayed in the exhibit. Worshippers expressed how Đạo Mẫu gives meaning, comfort, guidance, and a sense of continuity. One panel quoted: “When drinking water, remember its source” (Vietnamese idiom “Uống nước nhớ nguồn”), emphasizing gratitude, ancestry, and humility.

I also reflected on the fact that in 2016, UNESCO inscribed Mother Goddess Worship of the Three Realms on its Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage. That recognition underscores how unique and vital this spiritual-artistic tradition is, not only for Vietnam but for the world.

This field trip stirred in me a deeper respect for how beliefs live through art—through costume, song, dance, ritual—and how communities sustain them. The fact that hầu đồng remains practiced today—participated in by younger generations, evolving with modern life—speaks to its resilience and adaptability.

At the end, as we left the hall, I felt richer not in souvenirs but in insight. I carried with me images of changing costumes, the rise and fall of chầu văn melodies, and the devotion that knits past and present in this living tradition. This field trip showed me that the Mother Goddess worship exhibition is not just a museum display—it is a portal into Vietnam’s soul.